Noelle N. Trent is the Director of Interpretation, Collections, and Education at the National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. She wrote her doctoral dissertation at Howard University on “Frederick Douglass and the Making of American Exceptionalism.” She has presented papers and lectures at the American Historical Association, the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, and the European Solidarity Center in Poland. In 2018, she curated the exhibition MLK50: A Legacy Remembered, commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination.

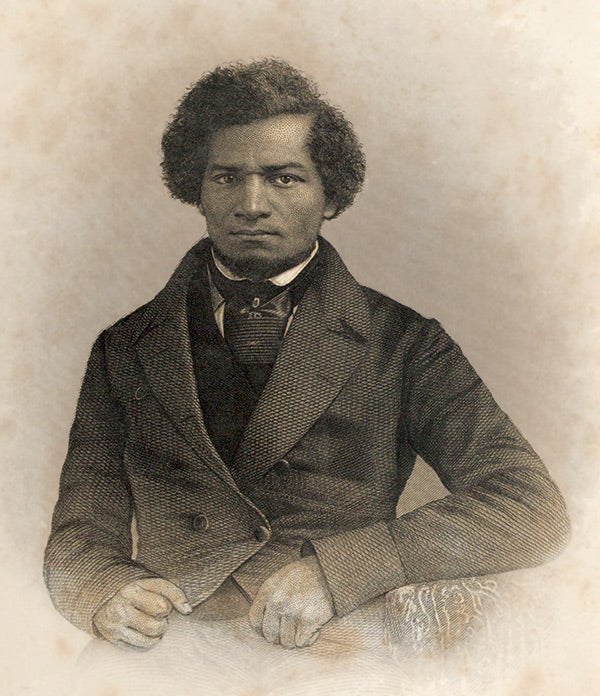

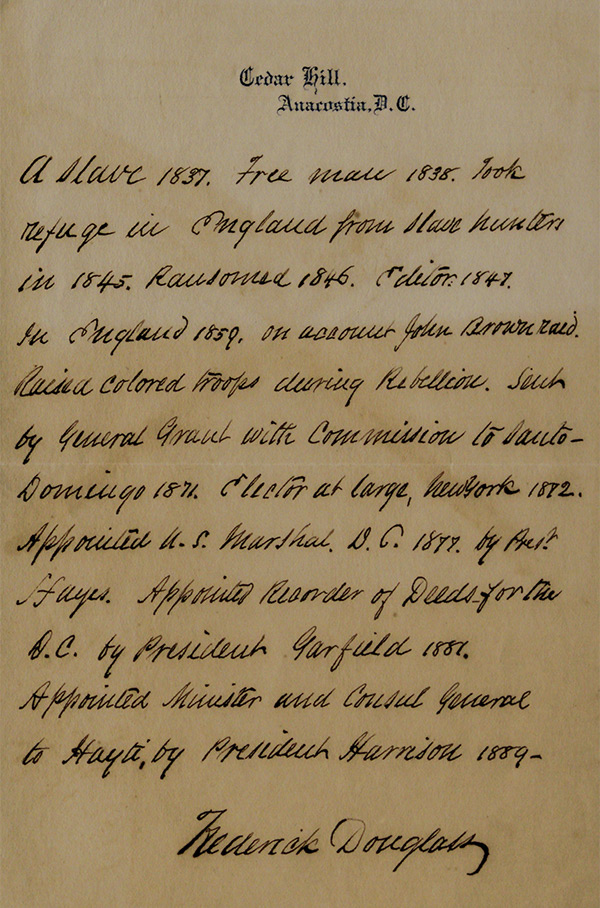

In 1893, approximately two years before his death, Frederick Douglass wrote a chronological summary of his life for one of his correspondents, Charles C. Pierce, a clergyman in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Douglass probably drafted the letter while sitting in his library at Cedar Hill in the Anacostia neighborhood of Washington DC.[1] Surrounded by hundreds of books, he might have glanced out the window at his estate, reflecting on the major achievements of his life, namely his transition from a person viewed as property to a public figure whose opinions were sought on national and international issues:

A slave 1837. Free man 1838. Took refuge in England from slave hunters in 1845. Ransomed 1846. Editor. 1847. In England 1859. on account John Brown raid. Raised colored troops during Rebellion. Sent by General Grant with Commission to Santo-Domingo 1871. Elector at large, New York 1872. Appointed U.S. Marshal. D.C. 1877. by Prest. Hayes. Appointed Recorder of Deeds for the D.C. by President Garfield 1881. Appointed Minister and Consul General to Hayti, by President Harrison 1889–

Frederick Douglass was by 1893 a firmly established self-made man and civil rights activist who would continue to fight for equality until his dying day.

Recounting the events of his life was not unusual for Douglass. He published three autobiographies: The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave (1845); My Bondage and My Freedom (1855); and The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881, revised 1892). Throughout his career, Douglass was an in-demand orator. His most frequently delivered speech was “Self-Made Men,” first delivered in 1859. At the time, the idea of the self-made man was very popular. The self-made man rose to success without the benefit of external advantage, or from obscurity on strength or personal merit. The self-made man was considered uniquely American because, according to the country’s founding principles, all men were created equal and there were equal opportunities for all. However, this idealized self-made man was a white man. African Americans and other minorities were excluded, and were subject to systemic oppression and racism. In his popular speech, Douglass challenged the prevailing social notions of the self-made man, demanding that his audience reconsider the intelligence and capabilities of African Americans and advocating the creation of a more equitable society.

Douglass’s celebration of the self-made man may seem very different from his other writings. However, in this speech he presented his life and the lives of his contemporaries as evidence of equality. As an enslaved child, Douglass was prohibited by law from learning to read and write. He received a few lessons from his mistress, Sophia Auld, but had to struggle to continue his education. Douglass traced the work in the notebooks of his owner’s son, Thomas, and bribed local boys to teach him. He later read the Columbian Orator, which helped him develop his public-speaking skills. Through his own ingenuity, Douglass became an educated man and a sought-after spokesman for the abolition movement.[2]

If Douglass and other black people could achieve success in the midst of slavery and entrenched racism, what more could they achieve in freedom? Douglass famously stated in his speech, “The nearest approach to justice to the Negro for the past is to do him justice in the present. Throw open to him the doors of the schools, the factories, the workshops, and of all mechanical industries. If he fails then, let him fail! I can, however, assure you that he will not fail. Already has he proven it. . . . Give him all the facilities for honest and successful livelihood, and in all honorable avocations receive him as a man among men.” [3]

Frederick Douglass loved the United States and believed in its principles. If the country was to remain true to its ideals, it would need to provide an opportunity for all men and women to succeed. But today, the types of discrimination Douglass fought still exist, from police brutality to the gender pay gap, to inequitable access to quality food, education, employment, and housing. In some ways, it’s difficult to take Douglass, a nineteenth-century man, and place him in the vastly different twenty-first century. However, inspired by Douglass, we can demand that resources and access be provided to all. Today people continue to succeed without such resources, but, as Douglass did, we must imagine what more we can accomplish. Like him, we also must remain activists throughout our lives.

For Douglass, the fight for equality did not end when slavery ended, and he did not fight only for African American men. Women’s rights was a lifelong passion. He had participated in the landmark women’s rights conference in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848 and signed the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments. On February 20, 1895, Frederick Douglass delivered his final speech to a women’s rights group in Washington DC. He returned to his Anacostia home for dinner with the intention of speaking at another engagement that evening. However, he collapsed in the foyer of Cedar Hill, and passed away a few hours later. Until his last breath, Douglass was concerned with improving the world around him. President Kennedy best described Douglass’s impact in 1961:

[Douglass] can give inspiration to people all around the world who are still struggling to secure their full human rights. . . . By advancing that cause through law, democratic methods and peaceful action, we in America can give an example of the freedom which Frederick Douglass symbolizes.[4]

As the twenty-first century successors to Douglass’s legacy, we should aspire to his standard.

This essay was originally published in the Gilder Lehrman Institute’s Frederick Douglass: A Life in Documents (2018).

[1] Douglass’s final home, Cedar Hill, at 1411 W Street SE, Washington DC, now the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site run by the National Park Service, is open to visitors.

[2] Frederick Douglass, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, 16–18, 86–88.

[3] Frederick Douglas, “Self-Made Men: An Address delivered in Carlisle Pennsylvania in March 1893,” in The Frederick Douglass Papers Series One: Speeches, Debates, and Interviews. ed. John W. Blassingame and John McKivigan, vol. 5: 1881–1893 (Yale University Press: New Haven, 1992), 556.

[4] John F. Kennedy to Rosa Gragg, March 2, 1961.