What comes to mind when you think of communication? The ways we verbally communicate in conversations and presentations? How about the ways we communicate through text, photographs, and videos on social media? Or maybe you think about how your attire and posture communicate something about who you are. These are just a few examples of how communication is all-encompassing and almost inescapable.

This book views communication as crucial and advocates for developing a knowledge base and skillset that will help you become more competent communicators in your personal, professional, and civic lives. As you read through this introductory chapter, you are encouraged to take note of aspects of communication that you haven’t thought about before and begin to apply the principles of communication to various parts of your life.

How would you define communication? What elements does your definition include? How would you visually illustrate your concept of communication? Throughout the years, there have been a wide variety of definitions and models of communication—some simple and some complex. This book defines communication as the process of generating shared meaning through the exchange of verbal and nonverbal messages. In the following section, we discuss some of the essential elements that make up communication, introduce three models of the communication process, and discuss the four primary forms of communication.

Although individual definitions of communication vary, those definitions often include some of the same essential elements. Seven important components of the communication process include participants, symbols, encoding, decoding, channels, feedback, and noise.

What are some elements of the communication process that your definition includes? Unless you’re thinking of intrapersonal communication (the act of talking to yourself), your definition probably includes two or more participants, the senders and/or receivers of messages. The messages those participants send and receive are made up of symbols, verbal or non-verbal signifiers that represent ideas and serve as the building blocks of communication. For example, when you say “Hello!” to your friend as a greeting, you are using a verbal symbol (a word) to convey your meaning. Alternatively, non-verbal symbols to greet someone could include a wave or a handshake.

The internal cognitive process that allows participants to send, receive, and understand messages is the encoding and decoding process. Encoding is the sender’s process of turning thoughts into messages. Decoding is the receiver’s process of taking and interpreting a message. Although these definitions make them sound like intentional, well-thought-out processes, the level of conscious thought that goes into encoding and decoding messages varies. In everyday conversation, encoding and decoding sometimes seem instantaneous. At other times, participants carefully choose every word they use in the encoding process.

An encoded message is sent through a channel, a medium through which communication occurs. Think of the various channels that you use daily. You speak to your professors face-to-face, you chat with friends through Snapchat, you talk to a family member on FaceTime, you watch an influencer’s videos on TikTok, or you scroll through posts on Reddit. Many of these channels allow for immediate feedback, any response from the receiver to the sender of a message. You might leave a comment on a YouTube video or ask a follow-up question to a teacher. Face-to-face communication is often considered the richest channel of communication, in part because of its allowance for immediate verbal and non-verbal feedback. Yet, all channels have their own strengths and limitations. For example, you can reach a large audience quickly on Twitter, but not all messages can be effectively conveyed in a text-based and character-limited Tweet.

As we know, there are often barriers to effective communication. Noise is anything that interferes with a message being sent between participants in a communication encounter. Even if a speaker encodes a clear message, noise may interfere with a message being accurately received and decoded. External noise includes any physical or audible noise present in a communication encounter. Other people talking in a crowded diner could interfere with your ability to transmit a message and have it successfully decoded. Internal noise includes stimuli in our minds or bodies that could detract from our ability to listen to and decode a message. If you were stressed about an exam or tired from a lack of sleep, you might not be able to effectively listen to a professor’s lecture.

To better understand communication, it may be helpful to visualize what communication looks like. After all, communication is a complex process. It can be difficult to determine where or with whom a communication encounter starts and ends. Models of communication simplify the process by providing a visual representation of the various aspects of a communication encounter. We will discuss three models of communication: the linear model, the interaction model, and the transactional model.

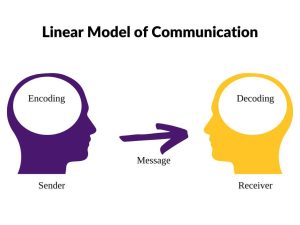

The Linear Model of Communication

The linear model of communication describes communication as a one-way process in which a sender intentionally transmits a message to a receiver (Ellis & McClintock, 1990). This model focuses on the sender and message within a communication encounter. Although the receiver is included in the model, this role is viewed as more of a target or end point rather than part of an ongoing process. As this model does not account for feedback, we are left to presume that the receiver either successfully receives and understands the message or does not.

Today, many view the linear model of communication as oversimplified or underdeveloped. But consider how the scholars who designed this model were influenced by the prevalent technologies of their time, such as telegraphy and radio (Shannon & Weaver, 1949). Think of how a radio message is sent from a person in the radio studio to you listening in your car. The radio announcer (the sender) transmits a message by a radio tower through electromagnetic waves (the channel) and eventually reaches your (the receiver’s) ears via an antenna and speakers. The radio announcer doesn’t really know if you received their message or not, but if the equipment is working and the channel is free of static (external noise), then there is a good chance that the message was successfully received. Since this model is sender and message focused, responsibility is put on the sender to ensure the message is successfully conveyed.

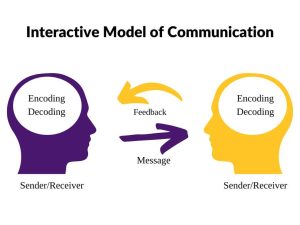

The Interactive Model of Communication

The interactive model of communication describes communication as a process in which participants alternate positions as sender and receiver and generate meaning by sending messages and receiving feedback (Schramm, 1997). Rather than illustrating communication as a linear, one-way process, the interactive model incorporates feedback, which makes communication a more interactive, two-way process. In the interactive model, each participant alternates roles as sender and receiver in order to keep a communication encounter going. Although this seems like a perceptible and deliberate process, we alternate between the roles of sender and receiver very quickly and often without conscious thought.

The interactive model is also less message focused and more interaction focused. While the linear model focused on how a message was transmitted and whether or not it was received, the interactive model acknowledges that there are so many messages being sent at one time that many of them may not even be received. Some messages are also unintentionally sent. Therefore, communication isn’t judged effective or ineffective in this model based on whether or not a single message was successfully transmitted and received.

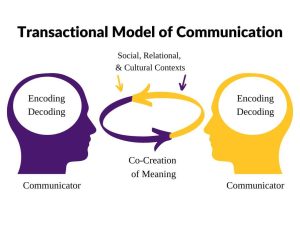

The Transactional Model of Communication

As the study of communication progressed, models expanded to account for more of the communication process. Many scholars view communication as more than a process that is used to carry on conversations and convey meaning. We don’t send messages like computers, and we don’t always neatly alternate between the roles of sender and receiver as an interaction unfolds. We can’t consciously decide to stop communicating, because communication is more than sending and receiving messages (Barnlund, 1970).

The transactional model of communication describes communication as a process in which communicators generate social realities within social, relational, and cultural contexts. In this model, we don’t just communicate to exchange messages; we communicate to create relationships, form intercultural alliances, shape our self-concepts, and engage with others in dialogue to create communities. In short, we don’t communicate about our realities; communication helps to construct our realities.

The roles of sender and receiver in the transactional model of communication differ significantly from the other models. Instead of labeling participants as senders and receivers, the people in a communication encounter are referred to as communicators that simultaneously send and receive messages. For example, on a first date, as you send verbal messages about your interests and background, your date reacts nonverbally. You don’t wait until you are done sending your verbal message to start receiving and decoding the nonverbal messages of your date. Instead, you are simultaneously sending your verbal message and receiving your date’s nonverbal messages. This is an important addition to the model because it allows us to understand how we are able to adapt our communication—for example, a verbal message—in the middle of sending it based on the communication we are simultaneously receiving from our communication partner.

The transactional model of communication also includes a more complex understanding of context. Since the transactional model views communication as a force that shapes our realities before and after specific interactions occur, it accounts for contextual influences outside of a single interaction. To do this, the transactional model considers how social, relational, and cultural contexts frame and influence our communication encounters.

Social context refers to the stated rules or unstated norms that guide communication. As we are socialized into our various communities, we learn rules and implicitly pick up on norms for communicating. Some common rules that influence social contexts include don’t lie to people, don’t interrupt people, don’t pass people in line, greet people when they greet you, thank people when they pay you a compliment, and so on. Parents and teachers often explicitly convey these rules to their children or students. Rules may be explicitly stated over and over again.

Conversely, norms are social conventions that we pick up on through observation, practice, and trial and error. We may not even know we are breaking a social norm until we notice people looking at us strangely or someone corrects or teases us. For example, as a new employee you may over- or underdress for the company’s holiday party because you don’t know the norm for formality. Although there probably isn’t a stated rule about how to dress at the holiday party, you will notice your error without someone having to point it out, and you will likely not deviate from the norm again in order to save yourself any potential embarrassment.

Relational context includes the previous interpersonal history and type of relationship we have with a person (Vangelisti & Crumley, 1998). We communicate differently with someone we just met versus someone we’ve known for a long time. Initial interactions with people tend to be more highly scripted and governed by established norms and rules, but when we have an established relational context, we may be able to bend or break social norms and rules more easily. For example, you would likely follow social norms of politeness and attentiveness and might spend the whole day cleaning the house for the first time you invite your new neighbors to visit. Once the neighbors are in your house, you may also make them the center of your attention during their visit. If you end up becoming friends with your neighbors and establishing a relational context, you might not think as much about having everything cleaned and prepared or even giving them your whole attention during later visits.

Cultural context includes various aspects of identities such as race, gender, nationality, ethnicity, sexual orientation, class, and ability. Whether we are aware of it or not, we all have multiple cultural identities that influence our communication. Some people, especially those with identities that have been historically marginalized, are regularly aware of how their cultural identities influence their communication and influence how others communicate with them. Conversely, people with identities that are dominant or in the majority may rarely, if ever, think about the role their cultural identities play in their communication.

Forms of communication vary in terms of participants, channels used, and contexts. The main forms of communication, all of which will be explored in much more detail in this course, are interpersonal, group, public, and mass communication. If you find one of these forms particularly interesting, you may be able to take additional courses that focus specifically on it. The following discussion provides a brief summary of each form of communication.

Interpersonal communication is communication between people whose lives mutually influence one another. Interpersonal communication builds, maintains, and ends our relationships, and we spend more time engaged in interpersonal communication than the other forms of communication. Interpersonal communication occurs in various contexts and is addressed in subfields of study within communication studies such as intercultural communication, organizational communication, health communication, and mediated communication.

Group communication is communication among three or more people interacting to achieve a shared goal (Powell, 1996). You have likely worked in groups in high school and college, and if you’re like most students, you didn’t enjoy it. Even though it can be frustrating, group work in an academic setting provides useful experience and preparation for group work in professional settings. Organizations have been moving toward more team-based work models, and whether we like it or not, groups are an integral part of people’s lives. Therefore, the study of group communication is valuable in many contexts.

Public communication is communication from one person to a large audience. Public speaking is something that many people fear, or at least don’t enjoy. Later in the chapter, we’ll learn some strategies for managing speaking anxiety. Compared to interpersonal and group communication, public communication is the most consistently intentional, formal, and goal-oriented form of communication we have discussed so far.

Mass communication is communication that is transmitted to many people through traditional and interactive media. Traditional media such as newspapers, magazines, radio, and television continue to be important channels for mass communication, although they have suffered much in recent years due to evolving technology and trends. Social media, streaming platforms, podcasts, and blogs are mass communication channels that you probably engage with regularly. The technology required to send mass communication messages distinguishes it from the other forms of communication.

Taking this course will change how you view communication. Most people admit that communication is important, but it is often in the back of our minds or viewed as something that “just happens.” Putting communication at the front of your mind and becoming more aware of how you communicate can be informative and have many positive effects. The following section discusses why and how we study communication. First, we provide a brief overview of the field of communication studies. Second, we describe the importance of communication competence.

As we learn more about the study of communication, you are encouraged to take note of aspects of communication that you haven’t thought about before and begin to apply the principles of communication to various parts of your life.

Communication studies is a diverse and vibrant field of study. Within a single communication program, you might find students and faculty who study communication in contexts as far-ranging as relationships, politics, science, sports, social movements, healthcare, and businesses. It’s likely that no matter what your specific interests are, you can find ways to explore them through communication theories and perspectives.

How did communication studies grow into such a rich and varied field? To begin answering this question, we can trace the study of communication to different ancient civilizations around the world. For example, in Africa, ancient communities conceptualized nommo, or the creative power of the spoken word (Asante, 1998). In China, Confucian philosophers were concerned about the ethical consequences of public speaking (Lu, 1998). In Greece, philosophers like Aristotle studied rhetoric, or the art of persuasive speaking. Today, the field of communication studies is enriched by these historical perspectives and elements of communication, along with many newer concepts, theories, and ideas.

As a discipline, communication studies stands out because of its practicality and ability to be integrated into our professional, personal, and civic lives.

Professional

Communication skills are consistently ranked from year-to-year as one of the top traits employers look for in the college graduates they hire (National Association of Colleges and Employers, 2022). Desired communication skills vary from career to career, but this textbook provides a foundation onto which you can build communication skills specific to your major or field of study. Research has shown that introductory communication courses provide important skills necessary for functioning in entry-level jobs, including listening, writing, persuading, communicating interpersonally, informational interviewing, and small-group problem solving (DiSalvo, 1980).

While communication studies courses can help students develop communication skills that will benefit them in any career, a major or minor in communication studies also prepares students for specific career opportunities, such as:

Personal

Many students know from personal experience and from the prevalence of communication counseling on television talk shows and in self-help books that communication forms, maintains, and ends our interpersonal relationships. While we do learn from experience, until we learn specific vocabulary and develop foundational knowledge of communication concepts and theories, we do not have the tools needed to make sense of these experiences. The field of communication studies gives us a vocabulary to name the communication phenomena in our lives, thereby increasing our ability to consciously alter our communication to achieve our goals, avoid miscommunication, and analyze and learn from our inevitable mistakes.

Civic

Civic engagement refers to working to make a difference in our communities by improving the quality of life of community members; raising awareness about social, cultural, or political issues; or participating in a wide variety of political and nonpolitical processes (Ehrlich, 2000). The civic part of our lives is developed through engagement with the decision making that goes on in our society at the small-group, local, state, regional, national, or international level. Such involvement ranges from serving on a neighborhood advisory board to sending an e-mail to a US senator. The field of communication studies is rife with concepts in persuasion, deliberation, media literacy, and conflict management that are critical to effective civic engagement.

Communication competence refers to the knowledge of appropriate, ethical, and effective communication patterns and the ability to use and adapt that knowledge in various contexts (Cooley & Roach, 1984). To better understand this definition, let’s break apart its three key components: appropriateness, ethics, and effectiveness.

Appropriateness

A competent communicator understands that they must adapt the way they communicate to make it appropriate for different situations. For example, someone texting a friend might use emojis and informal language without paying much attention to spelling or grammar. However, when sending an email to a professor, that same person will likely use a formal greeting, write in complete sentences, and double check their email for errors. While there may not be formal rules for how we should send texts vs. emails or how we should communicate with friends vs. professors, a competent communicator adapts their message based on the unwritten norms and expectations.

Ethics

Communication ethics deals with the process of negotiating and reflecting on our actions and communication regarding what we believe to be right and wrong. The emphasis in the study of communication ethics is on practices and actions, rather than thoughts and philosophies. Many people claim high ethical standards but do not live up to them in practice. A competent communicator prioritizes ethical communication practices such as truthfulness, fairness, integrity, and respect for self and others.

Effectiveness

Effectiveness refers to an individual’s ability to achieve their goals through communication. Knowledge, skills, and motivation are important factors in an individual’s ability to be an effective communicator. For example, you might know strategies for being an effective speaker, but public speaking anxiety that kicks in when you get in front of the audience may prevent you from fully putting that knowledge into practice (see Box 1.1 for strategies to deal with communication apprehension). It’s not enough to know what good communication consists of; you must also have the motivation to reflect on and better your communication and the skills needed to do so.

Key Concepts: Managing Communication Apprehension

Decades of research conducted by communication scholars shows that communication apprehension is common among college students (Priem & Solomon, 2009). Communication apprehension is fear or anxiety experienced by a person due to actual or imagined communication with another person or persons. This includes multiple forms of communication, not just public speaking. Some people get nervous in one-on-one communication settings, such as interviews or first dates. Others may fear speaking up in small group settings such as team meetings. Communication apprehension is a common issue faced by many people.

Seven Ways to Reduce Communication Apprehension

Discussion Questions:

Asante, M. (1998). The Afrocentric idea: Revised and expanded edition. Temple University Press.

Barnlund, D. C. (1970). A transactional model of communication. In K. K. Sereno & C. D. Mortensen (Eds.), Foundations of communication theory (pp. 83–92). Harper and Row.

Cooley, R. E., and Roach, D.A. (1984). A conceptual framework. In R. N. Bostrom (Ed.), Competence in communication: A multidisciplinary approach (pp. 11–32). Sage.

DiSalvo V. S. (1980). A summary of current research identifying communication skills in various organizational contexts. Communication Education, 29(3), 283–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634528009378426

Ehrlich, T. (2000). Civic responsibility and higher education. Oryx.

Ellis, R. E., & McClintock, A. (1990). You take my meaning: Theory into practice in human communication. Edward Arnold.

Lu, X. (1998). Rhetoric in ancient China, fifth to third century B.C.E.: A comparison with classical Greek rhetoric. University of South Carolina Press.

Powell, D. (1996). Group communication. Communications of the ACM, 39(4), 50–53. https://doi.org/10.1145/227210.227225

Priem, J. S., and Solomon, D. H. (2009). Comforting apprehensive communicators: The effects of reappraisal and distraction on cortisol levels among students in a public speaking class. Communication Quarterly, 57(3), 259–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463370903107253

Schramm, W. (1997). The beginnings of communication study in America: A personal memoir. Sage.

Shannon, C. E., & Weaver, W. (1949). The mathematical theory of communication. University of Illinois Press.

Vangelisti, A. L., & Crumley, L. P. (1998). Reactions to messages that hurt: The influence of relational contexts. Communication Monographs, 65(3), 173–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759809376447

Chapter 1 was adapted, remixed, and curated from Chapters 1 and 10 of Communication in the Real World: An Introduction to Communication Studies, a work produced and distributed under a CC BY-NC-SA license in 2013 by a publisher who has requested that they and the original author not receive attribution.